Game Studies

What is a Game?

The question of "what is a game" might seem straightforward, especially since we've all played games before. Yet, defining a game can be surprisingly complex. This question isn't confined to any one type of game—whether it's a board game, a card game, a sport, or a digital game, the essence remains the same. How would you explain what a game is to someone who has never encountered one? Think about some of your favorite games—how do they differ from other forms of entertainment?

Play: Sprouts

📝Critical Thinking | 🕒15 minutes | 📂Required File: none

This activity is designed to help students access the characteristics required to describe something as a game.

Discussion

As a group think about the game you just played, what makes it a game? What is required for something to be a game? How would you define a game?

Understanding what a game truly is allows us to appreciate them on a deeper level and even design our own. Scholars and game designers have proposed various definitions, each highlighting different aspects of what makes a game. As we explore these definitions, you'll notice some common elements that form the foundation of any game.

It is important to note that we will be discussing games as a whole, encompassing all types—traditional, physical, tabletop, and digital. The concepts and principles we explore apply to games in general, rather than focusing on any specific type.

Definitions of a Game

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word game is defined as

- "an activity which provides amusement or fun".

While this captures the essence of enjoyment, it's too broad to define what makes something a game. Turning to the Internet, Google's first definition describes a game

- "a form of play or sport, especially a competitive one played according to rules and decided by skill, strength, or luck".

This highlights the competitive and rule-based nature of games but still lacks the specificity needed for a comprehensive definition. Over the years, several prominent game designers and researchers have offered their own definitions of what constitutes a game. Here are a few widely cited definitions:

- "A series of meaningful choices ." - Sid Meier, game designer known for the Civilization series.

- "An activity among two or more independent decision-makers seeking to achieve their objectives in some limiting context ." - Clark C. Abt, game researcher and author of Serious Games.

- "A form of art in which participants, called players, make decisions to manage resources through game tokens in the pursuit of a goal ." - Greg Costikyan, game designer and author known for his work on game theory and design.

- "A closed formal system that subjectively represents a subset of reality, emphasizing the importance of rules and the systemic nature of games." - Chris Crawford, game designer and theorist known for his book The Art of Computer Game Design.

- "A type of play activity, conducted in the context of a pretend reality, in which the participant(s) try to achieve at least one arbitrary, nontrivial goal by acting in accordance with rules ." - Ernest Adams, game designer and author of Fundamentals of Game Design.

- "A system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome ." - Katie Salen & Eric Zimmerman, game designers and authors of Rules of Play.

Examining each definition, what similarities do you notice? Are there any key terms that keep appearing? Understanding these recurring themes will guide us in defining the key elements of a game.

Requirements for a Game

After examining the definitions above, we can conclude that certain elements are essential for an activity to qualify as a game. Therefore, all games must include the following:

Goal

All games require some sort of goal, which is essentially what the player aims to achieve. This is often the first question a game designer must ask when developing a game.

Clear goals are essential for players to understand what they need to do to win or progress. They provide purpose and direction to the gameplay, guiding players on their journey and shaping their experience. For instance, if the goal is to "achieve the highest score," this overarching aim gives players a clear target.

It's important to differentiate between goals and objectives, although the terms are often used interchangeably. Goals represent long-term aims, such as "achieving the highest score," while objectives are specific, short-term actions or milestones that help achieve these goals. For example, objectives in this game might include "collect all the bonus items" or "complete each level within a certain time limit." Objectives are the tasks players complete to move closer to reaching the goal. In game design, goals reflect the overall purpose or endgame, while objectives are the individual tasks or challenges needed to reach the goal.

Rules

Rules are the instructions that dictate what the player can and cannot do in order to achieve their goals. They define the boundaries and constraints within the game, setting limits on player actions and interactions.

An underlying element created by the limitations set by the rules, though not explicitly mentioned, is challenge. Challenge engages the player by requiring them to leverage the rules to reach their goal, making the process fun and rewarding. The concept of artificial conflict, as mentioned by Katie Salen & Eric Zimmerman, is a direct result of rule-based constraints at odds with the goal of the game, thereby creating challenges.

Rules should also provide a balance to the game experience by maintaining the viability of various strategies and ensuring that no single strategy or approach dominates the game. Balance ensures that all players have an equal opportunity to win or lose within the game based on their actions or meaningful choices, as mentioned by Sid Meier.

Outcomes

Outcomes are what the player's actions result in at the end of the gameplay, such as winning or losing. They must be uncertain, measurable, and often unequal, reflecting the varying levels of success or failure among players.

Although outcomes may be unequal, they should still feel balanced in relation to the rules of the game. This means that all players should have an equal opportunity to win or lose, given their actions within the game. Balance is not necessarily equal to fairness but the perception of fairness. For example, in many crane games, prizes are awarded at random intervals. Despite the randomness, players often perceive these games as balanced because everyone has an equal chance of winning. The key is that this balance must be perceived as consistent, fair, and fun to maintain player engagement.

Play and Pretend in Games

To better understand what constitutes a game, it's helpful to explore related concepts such as play and pretend. While these concepts are not specific elements of a game, they play a crucial role in shaping our understanding of what makes an activity engaging and enjoyable.

Play

The Oxford English Dictionary defines play as:

- Play: to engage in an activity for enjoyment or amusement.

You might notice that this definition is quite familiar. That is because the Oxford English Dictionary defines a game in a very similar manner

- Game: an activity that provides amusement or fun.

These closely related definitions underscore the similarity between play and games. While both involve activities for enjoyment, there is a key distinction: play refers to engaging in an activity for fun (i.e. enjoyment, amusement), which links to entertainment. In contrast, a game is a structured form of play that includes specific elements like goals, rules, and outcomes. This distinction is important because not all play qualifies as a game. Understanding this difference helps clarify why some activities that are enjoyable and interactive might not meet the criteria to be classified as a game.

Pretend

The concept of pretend is reflected in-game definitions mentioning a subset of reality or artificial conflict, in short, pretend can be defined as:

- Pretend: creating and engaging with a fictional reality through its rules.

Pretending is fundamental to many games, where participants immerse themselves in an imagined world by agreeing to operate within a set of fictional constraints. While pretending itself is not a game element, it complements the structured nature of games by adding a layer of imagination and creativity, enhancing the overall gaming experience.

Play: Maysu

📝Critical Thinking | 🕒10 minutes | 📂Required File: none

This activity is designed to help students identify puzzles and whether they qualify as a game.

Discussion

As a group think about the puzzles you attempted to solve. What are some differences between a puzzle and a game? Is a puzzle a game?

Types of Play Activities

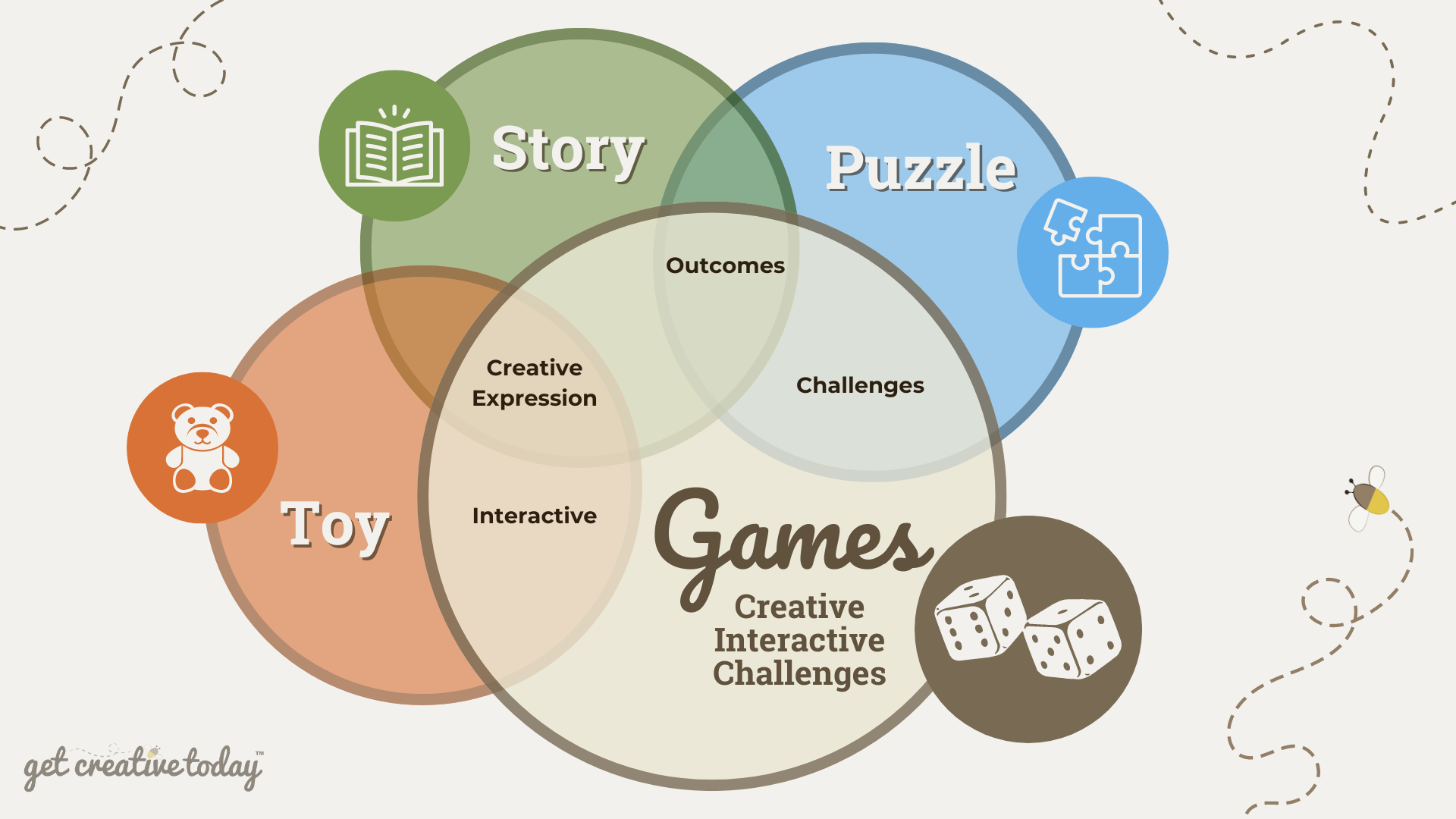

To fully understand what defines a game, it's essential to distinguish it from other types of activities such as stories, toys, and puzzles. This exploration helps us identify the fundamental characteristics that set games apart. While these activities share some similarities with games, such as having rules or providing engaging experiences, they each present distinct aspects that differentiate them. Understanding these differences will not only reinforce our definition of games but also illuminate the unique elements that contribute to the richness of the gaming experience.

Chris Crawford, a widely cited game designer and author of Chris Crawford on Game Design and The Art of Computer Game Design, provides valuable insights into these distinctions. Although his books focus primarily on computer game design, Crawford's comparisons are relevant to all types of games, not just digital ones. By examining how games differ from stories, toys, and puzzles, Crawford helps clarify what makes games unique and offers a broader perspective on game design.

Fig 2. Games have elements that overlap with other play activities such as stories, toys and puzzles.

Fig 2. Games have elements that overlap with other play activities such as stories, toys and puzzles.

Stories

Crawford describes stories as linear narratives with predetermined outcomes experienced passively. Although Crawford does not explicitly address this, stories also allow for creative expression from both the writer and the reader. The writer crafts the narrative, while the reader uses their imagination to interpret and experience the story. Reader engagement is further developed through passive challenges presented by the experiences of the protagonists, even though there is a fixed and predetermined outcome.

Toys

According to Crawford, toys are designed for creative expression through interaction but do not involve specific goals and have no real outcomes. Unlike games, toys do not present structured challenges; instead, their engagement is purely interactive. For example, playing with building blocks allows children to create various structures, fostering creativity and imaginative play and creativity without a predefined goal or outcome.

Puzzles

Puzzles, as Crawford notes, involve specific challenges that require problem-solving and strategy, engaging players intellectually. Puzzles generally offer a definitive outcome only when solved; if not solved, there is no resolution or progress. This clear-cut resolution contrasts with the ongoing, dynamic interaction found in games, which often includes uncertain outcomes and evolving challenges. The fixed nature of puzzles limits creative expression, as the problem-solving approach is generally uniform and does not evolve. Players receive feedback only upon solving the puzzle, which restricts their ability to explore various strategies and creative solutions. This lack of flexibility underscores how games, with their dynamic nature, provide a richer, more interactive experience.

Games

Crawford identifies the combination of interaction and structured challenges as a defining feature of games. Jacob Habgood and Mark Overmars, in The Game Maker's Apprentice, build on Crawford's perspective by defining games as interactive challenges. While this definition emphasizes interaction and structured challenges, it does not fully address the interplay between elements of stories, toys, and puzzles that Crawford highlights. Moreover, it overlooks how games facilitate significant creative expression by allowing players to apply different strategies and explore multiple approaches, which leads to uncertain outcomes.

Effective game design, according to Crawford, integrates aspects of stories, toys, and puzzles to create a more engaging experience. Therefore, games can be seen as comprising interaction, structured challenges, and creativity, which lead to uncertain outcomes. This combination sets games apart from other types of activities and significantly enhances the overall gaming experience.

Creative Interactive Challenges

While stories, toys, and puzzles each offer distinct forms of engagement—stories through passive challenges and creative expression, toys through interactive creativity, and puzzles through structured problem-solving—games uniquely blend these elements. Building on Habgood and Overmars' concept of "interactive challenges," a more comprehensive definition of games is creative interactive challenges . This expanded definition not only encompasses the interactive and challenging aspects of games but also acknowledges the significant role of creativity. By integrating creative expression, interaction, and structured challenges, games distinguish themselves from puzzles, stories, and toys, offering a multifaceted and enriched gaming experience.

Games as Systems

In our exploration of defining what a game is, we've encountered several instances where games are referred to as systems. A system is defined as a set of interacting or interdependent elements forming an integrated whole. By definition, a system requires all its elements to be present and working together to function properly.

As we've discussed, games require certain elements, such as goals, rules, and outcomes. They also involve the concept of play and pretend, as well as shared characteristics from other play activities. A game cannot exist without these (and other) interdependent elements interacting with each other, which, by definition, makes it a system.

Since a game is a type of system, we can look back at each definition we've discussed and assess that while they accurately describe a game by certain elements within the system, though not always specifying all elements.

Games Defined

After reflecting on the various definitions discussed in this chapter along with my own research, I have formulated a definition that encapsulates all these ideas to comprehensively define the term game.

"A game is an interactive system and type of play activity where players use creativity to overcome structured challenges in pursuit of a defined goal, while following the rules of a pretend reality, with their actions resulting in an uncertain yet measurable outcome." -Akram Tagahvi-Burris, game designer and educator.

This definition captures the essential attributes of games, including the interplay of creativity, structure, and player engagement. It will serve as a reference point as we continue to explore the deeper elements that make up the framework of games.

Studying Games

Now that we've thoroughly explored what defines a game, you might wonder why this matters. Most of us have played games and developed our own understanding of them. So, why delve into such detail, especially if you're an aspiring game designer with your own vision?

Understanding games in depth offers insights that extend beyond mere development. It equips designers with a comprehensive approach to crafting games that not only meet but exceed player expectations.

Ludology

The study of games isn't a modern phenomenon limited to video games and arcades. People have long been studying games from anthropology, psychology, literary, and most recently technological perspectives.

Ludology is the formal study of games, a term derived from the Latin words ludus, meaning "game" and logia, meaning "study". Ludology focuses on understanding games as systems and structures, examining their mechanics, rules, and gameplay experiences.

While ludology dates back to the mid-twentieth century, it gained attention in the late 1990s, particularly with Gonzalo Frasca's influential paper, "Ludology Meets Narratology." In this paper, Frasca argues that while games and narratives share similarities, they should not be studied under the same framework. He advocates for a distinct field of Ludology to better address the unique aspects of games. Although this text won't delve deeply into the Ludology vs. Narratology debate, it's important to recognize this discussion as a factor in the development of game studies.

Narratology is the study of narrative structure and its impact on storytelling. Narratology focuses on elements such as plot, character, and narrative techniques, examining how these components combine to create engaging stories across various media, including literature, film, and games.

Unlike narratology, which emphasizes narrative elements, ludology investigates how games function and how players interact with these systems, seeking to understand the unique aspects of games as interactive experiences.

Game Studies

The term Game Studies is widely used in academia, often preferred over "ludology." Although the study of games has been discussed since the early twentieth century, it wasn't until the 1990s, with the rise of video games—that "game studies" began to emerge as a distinct academic field. While much of the focus in game studies has been on video games, it is crucial to recognize that true game studies should encompass a broader exploration of games in general.

Ludologist is the term for someone who studies games (i.e., ludology). However, to the general public, this term might raise a few eyebrows. To avoid any confusion and keep things more straightforward, academics generally use Game Studies instead. .

In the foreword of Raph Koster's book A Theory of Fun for Game Design, game designer Will Wright remarked that "games are tricky to study because they are so multidimensional." He emphasized that game design involves various disciplines, including psychology, computer science, environmental design, and storytelling, among others. Wright argued that "to really understand what games are, you need to see them from all these points of view."

Game studies as an academic discipline, has been around for nearly 30 years,though it has yet to be regarded with the same prestige as other fields. One reason may be that game studies vary widely by program, course, and instructor. To further complicate matters, the discipline is often broken into distinct categories that study games from very different perspectives. These categories include game studies, game art, and game development. "Game studies" or "game design" often explore games primarily from sociological and psychological perspectives. Game art (sometimes also referred to as "game design") focuses on the skills required for creating game art (2D or 3D) as well as the aesthetics and creative expression within the field. Game development (or game programming) studies games from a technological standpoint, emphasizing the functionality of a game. However, it is through a mix of all these perspectives that games can truly be understood and appreciated.

For aspiring game designers, studying games from a holistic approach that examines all aspects of the discipline provides a clear image of what exactly a game is and how to design games that people want to play. Game designers who only focus on one aspect of the discipline might develop a profound game, but one that does not function well enough to be playable, or a game that is aesthetically pleasing with an engaging narrative but lacks meaningful interaction. Worse yet, they might create a game that is technically sound but simply not engaging to play at all.

In this text, we aim to study games through a scientific lens, breaking them down into their essential components, concepts, and the experiences of interacting with them. We will reverse-engineer and design games throughout this exploration to fully understand the question: What is a game?

Summary

This lesson began with the question, "What is a game?" While this might seem straightforward to anyone who has ever played a game, defining a game in its entirety is more complex than it first appears. Games are a form of play, yet they stand apart from stories, toys, and puzzles. They involve structured challenges, set within a system of goals and rules, but they also rely on players to engage and pretend. Moreover, games create interactivity through meaningful choices, which fosters emotional engagement. This complexity highlights the importance of Game Studies (formerly known as Ludology) as a field, underscoring the need for a comprehensive understanding of games to effectively study and design them.

Cited References

- Adams, E. (2010). Fundamentals of Game Design. Berkeley, CA: New Riders.

- Crawford, C. (1984). The Art of Computer Game Design. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Frasca, G. (2007). Play the Message: Play, Game and the Politics of Representation (PhD Dissertation, University of Amsterdam).

- Garfield, R. (2002). Characteristics of Games. In Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. New York: Wiley.

- Juul, J. (2005). Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Koster, R. (2005). A Theory of Fun for Game Design. Scottsdale, AZ: Paraglyph Press.

- Meier, S. (1994). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. New York: Wiley.

- Parlett, D. (1999). The Oxford History of Board Games. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.